AUSTIN, Texas (AP) — The NCAA waited nearly a year to issue a warning that there are still rules to follow now that college athletes can earn money off their fame, sparking speculation that a crackdown could be coming for schools and boosters that break them.

But the NCAA isn’t the only enforcement organization that stayed quiet as millions of dollars started flying around college athletes.

Nearly half the states, 24 in all, have laws regarding athlete compensation, all passed since 2019. Several specifically ban the sort of pay-for-play and recruiting enticement deals the NCAA still outlaws and critics of the new system worry about.

Yet those states have shown no appetite to question or investigate the schools, the contracts or the third-party groups orchestrating them. Even if they did, there is little legal framework for how they would do it.

Texas and Florida, two states with major college football and basketball programs, ban pay-for-play contracts and using deals to lure recruits to campus. But neither state set up mechanisms to investigate or punish a school, organization or agent caught breaking the rules.

“A lot of people are referencing the NCAA not taking action, but the same can be said about states,” said Darren Heitner, an attorney who helped craft the Florida law.

The unenforced state bans on pay-for-play and recruiting deals calmed lawmakers who worried that college sports they love were changing, said Heitner, an advocate for athletes’ rights to earn money. But there has been no indication a state attorney general or local prosecutor will go after a big university, coach and wealthy donors if the team is bringing in top players and winning.

Alabama was one state that did have specific punishment in its law: Anyone providing compensation to an athlete that caused them to lose eligibility faced a potential Class C felony, which carried up to 10 years in prison.

But Alabama lawmakers repealed the state’s entire college athlete compensation law earlier this year. The law’s original author called for the repeal because he worried it left Alabama schools at a recruiting disadvantage compared with rival schools in other states that didn’t have similar restrictions.

Arkansas gives some legal power to the athletes in that state. They can sue their agent or another third party that offers or sets up a deal later deemed improper and they are declared ineligible to play.

Half the states don’t have athlete compensation laws. Schools there have been left to navigate the general parameters the NCAA provided in June 2021 on the eve of the NIL era and to wait to see what would be enforced. Pay-for-play and “improper inducements” were still off the table, the NCAA said then, but there were few details and NIL deals were struck by the hundreds in the weeks that followed.

The NCAA finally stepped back into its enforcement role with new guidance that sought to clarify the types of contracts and booster involvement that should be considered improper.

Few expect a massive crackdown and the Division I Board of Governors noted that its focus was on the future. There’s simply too many athletes and too many contracts for NCAA enforcement to look at them all.

“The enforcement is going to fall on the NCAA, (but) there’s no way they’ll try to look at thousands of deals,” said Mit Winter, a sports law attorney in Kansas City, Missouri.

The NCAA will more likely look at some of the highly publicized deals set up through prominent business owners and third-party collectives that have popped up around dozens of schools to pool millions of dollars and connect athletes with business deals.

“It’s positioned itself where it has no choice but to try to make an example out of a booster or a collective,” Heitner said. “Otherwise, what was the point? … If it doesn’t, it’s powerless and obsolete. It still has that problem that it knows it is going to be sued.”

NCAA officials did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

At Texas, the nonprofit Horns With Heart raised eyebrows when it announced just before the December football national signing day that it would offer all Longhorns scholarship offensive linemen $50,000 NIL deals to support charities. A few days later, Texas signed one of the top recruiting classes in the country with a bumper crop of blue-chip offensive linemen.

Horns With Heart co-founder Rob Blair was unconcerned by the warning from the NCAA, saying the nonprofit has played by the rules since it launched.

“We realized at the beginning of the NIL era that this Wild West attitude would eventually lead us to a moment like this, that is why we set out to be different,” Blair said in an email. “We have gone above and beyond to ensure we not only follow the letter of the law of NIL regulation, but we feel we also represent the spirit of the NIL laws as they were originally written.”

Aside from NCAA enforcement staff, university compliance directors — long the watchdogs over athletes and their eligibility — are trying to navigate a shifting landscape with murky rules.

Lyla Clerry, Iowa’s senior associate athletics director for compliance, welcomed the NCAA’s renewed guidance on athlete endorsement contracts if it means they will be enforced.

“Honestly, I don’t know that I have a lot of faith that I’m going to see that happening,” Clerry said, noting the last year has been “frustrating” for compliance officials.

“You don’t really know, well, what should we be enforcing, because what is the NCAA going to enforce? So we can’t constantly be beating our heads trying to enforce things that nationally aren’t getting enforced,” Clerry said. ”I don’t know if I would say it’s operating blindly, but we’re definitely in the dark.”

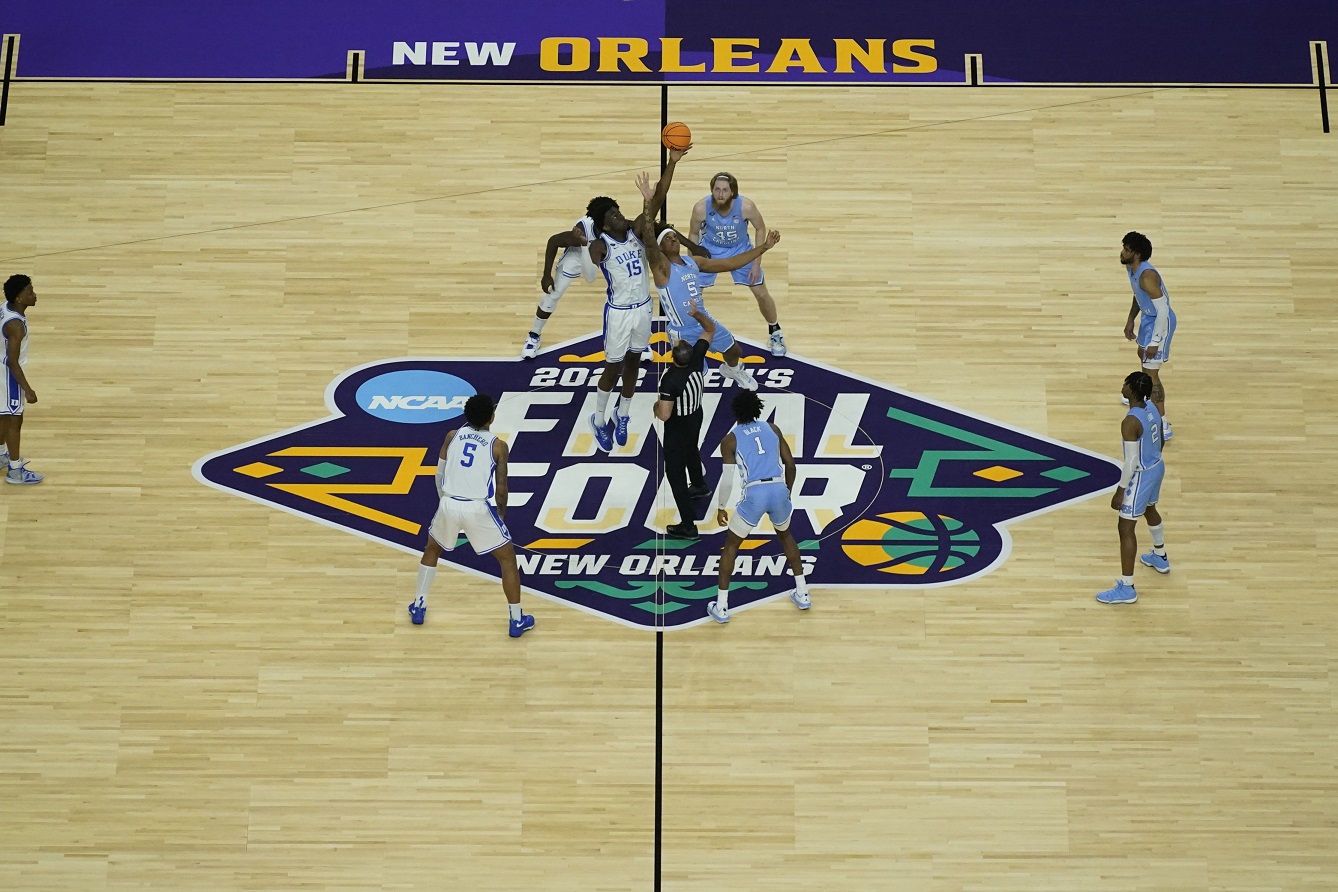

TOP PHOTO: FILE – Duke center Mark Williams (15) and North Carolina forward Armando Bacot (5) tipoff the first half of a college basketball game in the semifinal round of the Men’s Final Four NCAA tournament, Saturday, April 2, 2022, in New Orleans. (AP Photo/David J. Phillip)

More AP sports: https://apnews.com/hub/sports and https://twitter.com/AP_Sports